“Haunting describes those singular yet repetitive instances when home becomes unfamiliar, when your bearings on the world lose direction, when the over-and-done with comes alive, when what’s been in your blind spot comes into view.”

Family Turns

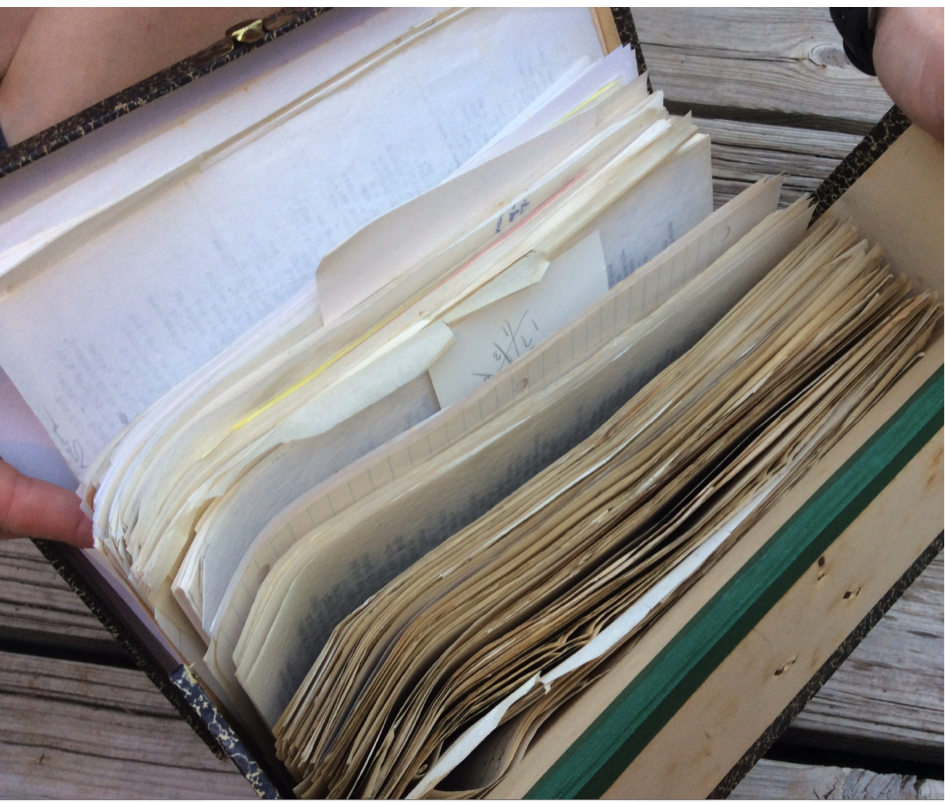

A series of family turns has rendered me steward of an unusual collection of letters which a relative of ours preserved for decades. This epistolarium, this accidental archive, consists of correspondence exchanged among his various siblings, some brothers and a sister, during their adult years. Some bundles of letters span forty years of communication. Strikingly, the writer, at times, nestled carbon—and later photo—copies of his own responses next to their letters. He preserved these epistolary ties to his family in weathered brown boxes, six or seven total, which he labeled neatly with the initials of each writer and recipient. He filed many in chronological order. Also scattered among the slips of fragile paper, yellowed clippings, and handwritten notes were loose photographs cast in grey and milky hues representing a sea of faces gazing out into the space around them or at each other, fleeting life moments—perhaps not of the subjects’ choosing—concretized in film. When I first encountered these boxes, they seemed haunted by my relative’s embodied presence . . . his familiar handwriting, his penchant for order, his investment in quality products that would stand the test of time. Even now, although I never observed the act, I can imagine his tall frame leaning in to place those initials in black ink, carefully, intentionally, across the spines of each of those brown boxes that now inhabit space in my home.

“Evocative Objects.” Photograph and caption by Lucy E. Bailey. Personal collection.

Although these letters are currently in my “possession”—if one could consider such objects possess-able—I have circled around them with little sense of familiarity and ownership and great ambivalence because they seem haunted, as Cvetkovich writes of any archive, “by the specter of death.” Haunting, Gordon suggests, “alters the experience of being in time, the way we separate the past, the present and the future.” I only hold these letters because “he” no longer does, as they were hauled en masse from his shelves when the writing from his siblings stopped and the inevitable time came when he could no longer sort, hold, and savor them. And it was only years after all of the writing stopped that any of us knew the letters existed at all. I don’t think he hid them; but he would not have felt compelled to discuss them widely with others, as these were his own “evocative objects,” his own archive, saturated with his own affective epistemologies, his own webs of relation. Under my gaze, with my own historical, affective and archival preoccupations rooted in non-positivist research approaches in a different period and context, the meanings of these boxes shift.

Analytical and Theoretical Choices

As I have pondered the haunting presence of these boxes and pages and photos that hover in the periphery of my vision, my mind has wandered through the theoretical terrain available for framing such objects and the potential paths I might follow to make sense of them. To pursue a particular analytic trajectory with historical materials is an act of power, a choice that frames and excludes, that “lights” certain things up while leaving others in shadow. And power operates because the researcher/descendant/archivist still lives, however temporarily, with access to such objects while “they” no longer do. The very stuff of history is built from centuries of historians and biographers and family members designating “what ‘counts’ as archival material worthy of study” and grappling with decisions about when to share, what to say and how to frame, and in the end, moving forward with their arsenals of available tools and partial materials to craft some kind of meaning. And inevitably, most will make choices about what to say and how to frame without access to the wishes of those who produced the objects, perhaps embracing such absences with relief, as a convenient form of consent for us to proceed at will with our analytic business, or, considering their wishes as simply less important overall than our lust for archival materials and our hopes and convictions as relatives/historians/biographers that such documents might prove valuable to ourselves or others.

I do not know what “his” wishes were, and I do not know yet what value these documents might have for broader educational matters. Carolyn Steedman suggests that archival materials such as these are “nothing,” Naomi Norquay reminds us, until they are taken up as objects of inquiry, as sites that matter. Certainly, at the very least, the appearance of these objects offers me a role as an “accidental archivist” should I choose to fully embrace it, and materials for cultivating a “narrative inheritance,” should I choose to subject them to a type of analysis that might enhance our inter-generational script of family identity. As Goodall writes of his own quest to understand his father’s mysterious life as a spy in his work, A Need to Know, narrative inheritances are important ways of making sense of self and family. “What we inherit narratively from our forebears,” he writes, “provides us with a framework for understanding our identity through theirs.” Goodall approaches the content of letters and other documents as vehicles to access and craft this inheritance, however partial. He felt he “needed” to do so. This theoretical approach is perhaps the most organic and realist choice I might make—to imagine these boxes as salient objects of a genealogical gaze and potential contributors to a family legacy. I didn’t “know” these relatives, these ancestors, and I could choose to analyze their letters as “windows” into their lives.

Humanist Investments in Objects

Yet this is only one choice one might make with this epistolarium; and the limits of such realist framings are apparent. The recent theoretical turns to affect and materiality that compel new ways of conceptualizing material aspects of the world and of undertaking historical work reminds us that we relentlessly construct such documents and objects in humanist terms: how humans used them, what they reveal about humans, what relationships among humans they fostered. The very hauntings and imaginings with which I introduced this essay are examples of such constructions, and offer particularly powerful framings because such “family” epistles are saturated with the potent cultural and nostalgic weight of bloodlines. They are the stuff from which family histories are constituted. I have written previously about the discursive power of “bloodlines” that shapes inquiries that happen to involve “family” members. As I have suggested elsewhere, “family” and “family histories” are constructed entities borne of discourses of belonging, the politics of representation, and differential racialized, classed, and gendered access to a narrative inheritance; our ability to create them depends on patterns of orality and literacy, privilege and erasure, and the eccentricities and politics of documentary survival: attic trunks and turns in stairwells. The extent to which “family” is a salient concept in such endeavors depends on varied factors including researcher-subject relations, theoretical investments, and project purpose—whether, for example, the particular project is on, with, or simply through the materials family members’ leave behind. My relative’s letters raise similar methodological complexities.

Yet inquiries “with” such documents do not necessitate analysis focused on “family,” or using family methodologies, and affective investments in historical objects, of course, need not depend on constructed “family” connections at all. Scholars have long-noted the ease of “falling in love with their subjects” through the material remnants of their lives and the range of analytic lenses available in making meaning. In the case of letters, scholars have considered their instrumental functions that “we” use or that “they” used in the past to inform, to communicate, to connect. Such objects can connote meaning beyond their denotations, signaling care, commitment, affection, and relational investments through sustaining key linkages with others. Such objects might function as evocative companions accompanying us on our life journeys that serve as touchstones for and storehouses of meaningful life events. They might have functioned this way for my relative, as they have for many others. Or, we might consider letters as intimate objects we feel at “one” with—such as we might with wedding rings, our father’s watch, our pacemakers, our photographs—entities we experience as extensions or fibers of our own bodies.

And, via Foucault we might also consider how the power relations and discourses in which “letters” and “family letters” are situated and which remain from others’ labor and care produce and discipline subjects—in this case—potentially he as a sibling in a web of emotional relations and me as a descendant and accidental and potential archivist. Academic and family discourses shape in powerful ways how we might understand and theorize personal letters and relationships as legitimate objects of knowledge. And, still further, we can consider such objects as commodities which we barter and exchange in particular emotional, political, market and/or academic economies. These rich options for theorizing objects do not exhaust their conceptual potential.

New Materialist Possibilities

Given the common humanist framings that shape our relation to objects, theorists of the new materialisms underscore our struggles to conceptualize or allow objects to have biographies and histories of their own that transcend their supplemental, symbolic, and utilitarian meaning granted through human use. Our anthropocentric orientation conceptualizes the various material objects that we encounter, utilize, embrace, and carry with us on a daily basis in terms of their meaning and function and service for our own lives rather than as having a coherent subjectivity and ontological thingness that exists beyond, alongside, or outside of human use. How might we think differently about objects? How might we consider a world of objects, of matter, without us? Or as matter that, in fact, makes us? And what does such framing mean for theorizing those haunted brown boxes inhabiting, however temporarily, the same space in which I reside?

Biographies of Objects

If I was to write a biography of these objects—not based on their content, their constructed role as epistolary remnants of a life, or as part of a discourse of family “belonging” I might imagine and pursue, but their materiality, the essence and history of their thingness—I would have to begin from a different set of questions and imaginaries. I would have to consider the “origin” of the objects themselves: how they came to be, perhaps, through the growing of seeds, the felling of trees, the processing of lumber, the creation of pulp, the passing through machines, through factories, through nameless men’s hands to become “paper;” then bound, carried, sold or exchanged in local economies, and eventually coming to inhabit space with a man who selected, stored, used, exchanged, and transported them across states and years, where they were imprinted, read, re-read, re-filed, re-shelved, moving through, with, and out of the hands of people who I will never know—and bearing still today the physical traces of their very skin cells. In this journey, the objects shifted and changed as people touched them, handled them, read them, and inscribed elements of their bodies into the ink as they bent over and pressed their pens into the pages. The pages changed form and color, becoming tattered, yellow, and worn. At the same time, the objects chafed and dyed the flesh of the hands that held them, merging the matter of flesh and of fibers together as they moved in and out of spaces and receptacles in their mutual becoming.

In this view, “objects have life roles that are multiple, fluid” beyond their human use. The “worn,” “tattered” objects I call “letters” or an “archive” are still evolving through, with, and beyond me, and my own constructed investments are only partially relevant to their becomings. In such a biography of objects I would have to consider that as these entities rest in the dust and pollen and heat of their environs and move through my hands and mingle with my own skin cells they—and I—change further, shifting, transforming, deteriorating, leaving traces of my ancestors’ bodies on my own before they move through and out on their papyrological journeys to other encounters. I simply serve as an instrumental and temporary steward; one small force in their becoming, and their materiality one small force in my own. If these trees-then paper-then letters-now archives have their own biographies, then they are not and cannot be “mine” despite the weighty presence they have in my pondering; contributing to forming me in passing, and perpetually transforming and becoming.

Ancestral Hauntings and the Politics of Obligation

I wonder what my relative would have thought of this ontological and post-humanist framing; I cannot shake the sense that this archive is haunted by the presence of the dead and my ancestor’s own epistemological investments. Such documents unsettle boundaries among past, present, and future. And here the theory of affect surfaces again in my thinking, as “affect makes a document significant.” Such documents unsettle boundaries among past, present, and future. I wonder whether in deciding which theory of epistolarity or materiality or biography I might choose to make meaning of these objects the ethical imperative arises for me to consider what the man who preserved them might have wanted. How did he theorize and experience these objects? Why did he preserve the collection? Did he hope for it to become a memory bearer? To create a future for the letters beyond his temporal existence? What did he want them to do for “us,” those who came after? I wonder about the careful marking of the boxes, their uniformity, their ordering. Were these careful archival machinations only for his own satisfaction—to care for objects as his parents had taught him? Or, might the preserving and arranging and labeling reflect a form of historical, archival, and pedagogical work—the possibility that he wanted others to read them, learn from them, remember those who came before, and make new meaning? As Cvetkovich writes: “at the heart of the archive are practices of memory.”

This trajectory of thought foregrounds the politics of obligation at work in preserving and sharing and serving as a steward of material objects. In Mauss’s early research on gift exchanges, he insisted that a gift that enters one’s life (in this case a happenstance gift of letters), “imposes obligation in the present . . . the thing received is not inactive. Even when it has been abandoned by the giver, it still possesses something of him . . . there is a succession of rights and duties to consume and reciprocate, corresponding to rights and duties to . . . accept.” In this perspective, gifts are always tied to social relations, to the individuals who give and receive the gift. Indeed, my relative’s intent may haunt the gift. And Norquay reminds me that my “archivist status is bequeathed, an inheritance, one might say, not something that [I] chose.” The politics of obligation may require that these letters remain on a shelf, under theorized, their content read solely by family members, if his archival intent was to prioritize their constitutive nurturing of webs of family relation over their other semiotic and historical potential.

The methodological and interpretive complexities I narrate here shape all such work “with” and “on” “family” documents, both complicated and perhaps nourished by the conflicting roles a researcher/family member/archivist simultaneously inhabits in the endeavor. In this case, I do not yet know the choice I will make—the picture has not yet come fully into view.

Naomi Norquay of York University and Thalia Mulvihill of Ball State University served as peer reviewers for this essay. Education’s Histories is grateful for their careful attention to and thoughtful feedback on this essay.